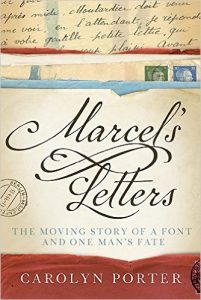

Marcel’s Letters: A Font and the Search for One Man’s Fate by Carolyn Porter, is the incredible story of her search to uncover the mystery of one man’s fate during WWII. Skyhorse Publishing will release it this June. Today is the last day to enter a Goodreads Giveaway for a free copy. Recently, I interviewed Carolyn about the backstory to writing her new book.

Marcel’s Letters: A Font and the Search for One Man’s Fate by Carolyn Porter, is the incredible story of her search to uncover the mystery of one man’s fate during WWII. Skyhorse Publishing will release it this June. Today is the last day to enter a Goodreads Giveaway for a free copy. Recently, I interviewed Carolyn about the backstory to writing her new book.

Jill Swenson: When you first sent me your manuscript almost two years ago, I confess I got goose bumps when I read it. I’d likely been to the antique shop in Stillwater where you’d found the letters since my sister lives there. My fascination with unknown aspects of World War II hooked me immediately into the story. That I am a big fan of letters and penmanship isn’t something you would have known, but it felt as though the story had found me in the same mystical way Marcel’s letters had found you.

Who was Marcel Heuzé and why are these letters you found so remarkable?

Carolyn Porter: Marcel Heuzé was an ordinary French civilian swept up in the barbarism of World War II. In January 1943, Marcel was sent to Berlin as part of a mandate to fill the Germans’ need for laborers. The camp where Marcel lived was comprised of wood-and-stone barracks, surrounded by razor wire, and guarded by SS. The camp is also where he penned letters to his wife and daughters; letters that contain the sweetest words of love imaginable combined with brutal descriptions of survival inside the camp.

Carolyn Porter: Marcel Heuzé was an ordinary French civilian swept up in the barbarism of World War II. In January 1943, Marcel was sent to Berlin as part of a mandate to fill the Germans’ need for laborers. The camp where Marcel lived was comprised of wood-and-stone barracks, surrounded by razor wire, and guarded by SS. The camp is also where he penned letters to his wife and daughters; letters that contain the sweetest words of love imaginable combined with brutal descriptions of survival inside the camp.

His letters initially caught my eye because I was looking for a handwriting specimen I could use as the basis of a computer font. I could not read his letters — they were written in French — but for the purposes of the font, that did not matter. An ‘a’ in French looks like an ‘a’ in English after all.

Even without being able to read what was in the letters, I knew they had been written with affection. You can see it in the care he took with his writing. His penmanship was undeniably alluring.

Jill Swenson: You began to search for information on Marcel’s fate. Where did you start and what did you find?

Carolyn Porter: Even before focusing on his fate, I needed to learn who he was. For example, at first, I wondered whether he had been a French prisoner of war. I assumed it would be easy to find the answer, and I began by typing his name into Google’s search engine. Initially I did not have much to go on: I had his full name, the first names of his daughters, an address in Berlin, and an address in France. I didn’t even know his wife’s name, as he only ever called her, “my darling.” Eventually I found one puzzle piece, then another. My curiosity intensified after every new puzzle piece.

I eventually exhausted every way I knew of to try to find information on Marcel’s fate. I wrote to every organization I could think of. I looked at every online resource I knew of. I ultimately got to a point where I had to face the fact I might not ever find the answers. It was at that point, it seemed, the Universe conspired to lend a helping hand.

Jill Swenson: The woman who translated the letters from French is a character with her own World War II story. It was wonderful to meet her over lunch with you in Stillwater, Minnesota, last year. Tell us about your friend, Louise.

Carolyn Porter: I just talked with Louise about an hour ago! Louise has singularly redefined how I think about aging. She is 91, but sometimes she acts like a twenty year old. Sometimes we talk about long-ago history (she was born in Paris and lived there through the occupation); other times we talk about modern things like politics, the allure of bad boys, or make-up trends (she doesn’t understand why more young women don’t wear lipstick). Last fall she was lamenting the flatness of her derrière, so I offered to buy her underwear with padded butt inserts. She laughed for five minutes straight, then said “OK, why not?!”

People find it odd that I choose to hang out with a 91-year-old — until they meet Louise! She is one of the most joy-filled, inspiring people I’ve met.

Louise was invaluable during the translation process because she could put things into context, such as the fact writing paper was rationed, and that Gare de l’Est was the train station that handled trains departing to Germany. Louise’s personal story is heartbreaking; she also helped me understand the reality of the many French men who disappeared and were never heard from again.

Jill Swenson: Are there more letters out there?

Carolyn Porter: Yes! I hope someday more of Marcel’s letters are found!

Jill Swenson: Writing about typography and computer fonts sounds rather dry and technical, but this story about how you designed the P22 Marcel Script is anything but dull. In the book, your husband Aaron pokes fun at the type geeks. But it’s true. You are a type geek. Last fall you went to a conference at the Hamilton Wood Type & Printing Museum in Manitowoc,Wisconsin. You stopped in Appleton on your way from the Twin Cities. We had dinner together and your enthusiasm for the festival was contagious. Why are you so passionate about typography?

Carolyn Porter: I’m proud to be a type geek! What’s funny is that I’ve heard non-typography people  offer the whispered confession, “I’m a closet font lover,” when they learn about this book. So, I think there are lots of undocumented type geeks out there.

offer the whispered confession, “I’m a closet font lover,” when they learn about this book. So, I think there are lots of undocumented type geeks out there.

In college I had a mandatory “Letterform” class, which ignited a love of letters and gave me a vocabulary to talk about shape and form. My professor, Professor DeHoff, made me understand that letters were as individual as a human body: they can be lean and graceful; they can be bold and bulge in unpleasant ways; they can be stately and refined; they can be irreverent; they can be quirky and funny; they can take your breath away with their beautiful proportions.

I have a special love of old-timey handwriting, which I understand is a ridiculously impractical thing to love. But, I can’t help it! To me, there are few things more beautiful than a page filled with scrolling script handwriting.

Jill Swenson: How did you find the narrative arc to this memoir? You have two stories which dovetail. Yours about finding Marcel’s letters and designing a font, and his story revealed in letters from a Nazi labor camp.

Carolyn Porter: Since I lived the story, and was committed to the book being a work of non-fiction, much of the “arc” was pre-defined. What I did, though, was make decisions about structure. For example, I knew I wanted the book to begin in July 2011 with the translation of the first letter, and I knew how I wanted the book to end since there is a logical ending “scene.” I drew a mental line between the beginning scene and the ending scene, and figured out how to structure all the things that happened in between (which includes events that happened seventy years earlier and things that would happen in the future).

Early on, I made additional decisions about what I wanted the book to be. For example, I wanted Marcel’s letters to speak for him; I did not want to invent dialogue for Marcel. I’m not a historian, so I wanted to help people understand World War II forced labor without the book reading like a textbook. And I wanted the place where Marcel’s wife and daughters lived — the French farming village of Berchères-la-Maingot — to be a “character” in the book.

Jill Swenson: Your book required some understanding of the law, including international laws, to proceed with publication of it. What did you learn about copyright and intellectual property as you worked on the licensing of the font and the publication of the book?

Carolyn Porter: Trust me, I spent more money on lawyers than I would have cared to!

Early on, I learned that the font based on Marcel’s handwriting and Marcel’s original handwritten letters were two very different things, legally. Handwriting, unless it is part of a trademark (envision the stylized Eddie Bauer signature logo) cannot be legally protected. If I wanted to, I could take a sample of your writing, turn it into a font, name it “Jill Swenson” and you would not have any legal recourse. Even though the style of handwriting can’t be copyright protected, the computer code that defines a font can be copyrighted, which is an important distinction. (Separately, a trademark on my font is working its way through the lengthy U.S. trademark system, which offers protections above and beyond copyright of the computer code.)

Marcel’s original handwritten letters, I learned, are subject to complex French privacy laws. Physical custody of the letters is immaterial; the fact I purchased the letters does not mean I have the right to publish the contents. Since parts of Marcel’s letters were to his daughters, the letters are subject to their privacy protections. The contents of Marcel’s letters can only be published because I have the written approval of his daughters (approval which took nearly a year to secure).

Jill Swenson: There were times on this journey to publication when you doubted whether this would ever be published. There were times when you didn’t think you’d finish the font. Yet it won awards and international recognition. What advice do you have for writers who seek publication?

Carolyn Porter: You have to be fully committed. Fully. Committed. That doesn’t mean the project has to be fast — in my case the font took twelve years, and the book took three more — but the story has to reside so deeply inside your bones that it isn’t an option for the story not to be told. Anything less will make it too easy to get discouraged and stop before your book finds life.

The possibility of publishing a book really came into focus once we started working together. I had never heard of a book development editor before, but working with you transformed the project from a far-off dream to an actionable reality. You’re a voracious advocate for the authors you work with, which is such a comfort — particularly to first-time authors.

Can I tell readers your nickname? Aaron and I refer to you as my “literary Sacagawea.” As in, you’re fearlessly leading me through this foreign forest called “getting published.”

Can I tell readers your nickname? Aaron and I refer to you as my “literary Sacagawea.” As in, you’re fearlessly leading me through this foreign forest called “getting published.”

Jill Swenson: I’m flattered by the nickname. When you were a child you had a calligraphy set that fascinated you. You say you didn’t know anything about how to design a font but you did it anyway. When you were a child, what books did you read that made you think you could write this story even if you didn’t know anything about being a writer?

Carolyn Porter: As a kid, I remember my mom taking me to the nearest library in Verona, Wisconsin, and helping me check out stacks of books. I can’t recall a specific book that made me think I could write a book, though I wrote a lot as a kid. I even wrote a play that classmates put on in fifth grade. We wore my mom’s old prom dresses and I recall one of us recited the line, “The Yankees is comin’.” Obviously, this was years before I learned the terms ‘vernacular language’ or ‘plagiarism.’

When the possibility of writing Marcel’s Letters came up, I was informally approached by three writers who expressed interest in writing the book. As I thought about it, though, I was unsure whether the first writer could capture my love for typography since they didn’t know anything about the field; another was a romance writer and I was unsure if they were interested in addressing the brutality of forced labor; the third was a pure historian and I was worried the book would go too deep into the details of World War II at the expense of making Marcel a relatable person. I had a vision of striking a balance between typography and history. I wasn’t sure how that balance would be achieved. I only knew that finding that balance would be key. I am a better writer than I am an extemporaneous speaker, and I realized if I partnered with any author I’d want to write up notes, timelines, feelings, etc. I ultimately decided if I’d be writing everything up anyway, I might as well write the book.

I knew I needed technical help, so I went to a week-long writing retreat and took several classes at the Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis. Those resources helped me develop the skills to feel like writing this book was possible.

I knew I needed technical help, so I went to a week-long writing retreat and took several classes at the Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis. Those resources helped me develop the skills to feel like writing this book was possible.

Jill Swenson: What books did you read while writing this book that affected your writing or revisions most deeply?

Carolyn Porter: I have shelves filled with books on World War II, French history, and forced labor. All of those were important to understand Marcel’s circumstances. Some of those books are dry, academic tomes. Others are memoir. All were important as I considered how to structure Marcel’s Letters.

I balanced those books with books on writing craft; books such as Stephen King’s On Writing, and Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird.

Jill Swenson: If you were to provide the musical score to your book, what would it be?

Carolyn Porter: I love this question! Several pieces of music are mentioned in the book: era-specific songs by Maurice Chevalier and Edith Piaf, along with the French national anthem. As I was writing the middle of the book (the point in time when I was exhausting every possibility of finding Marcel) I listened to Olafur Arnalds. The moody, ethereal tracks of “Alice Enters,” “Poland,” and “The Wait” captured the agony of the answers’ absence.

Jill Swenson: What are you working on next? Are there more books about letters from France during the war?

Carolyn Porter: I’m generally a happy person, but writing about a World War II forced labor camp certainly led to some dark days. Aaron has proclaimed that if I write another book, it needs to be about rainbows and puffy clouds and unicorns — or at least something light-hearted that won’t give me nightmares. I have an idea for a second book, but I expect my next project, actually, will be another font. I haven’t had time to design type while I’ve been working on the book and I miss it. Perhaps I’ll name my next font “Unicorns and Puffy Clouds.”

Jill Swenson: When and where is your book launch?

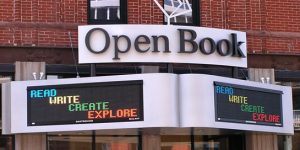

Carolyn Porter: The book’s publication date is June 6. On the evening of June 8, we’ll be having a party at Open Book in Minneapolis. I can’t guarantee this, but it’s possible a few of Marcel’s original letters will be on display.

Carolyn Porter: The book’s publication date is June 6. On the evening of June 8, we’ll be having a party at Open Book in Minneapolis. I can’t guarantee this, but it’s possible a few of Marcel’s original letters will be on display.

The event should be a delight because many of the people in the book will be there; it will be fun for people to put a face with a name. It’s open to the public — join me!

Jill Swenson: Thanks, Carolyn. To learn more about Marcel’s Letters or connect with Carolyn Porter, visit her website and sign-up to receive news about the release and author events.

Thanks for this great interview. The book sounds fascinating. I’ll be looking for it!