When you write a book length manuscript you need to keep the story moving forward. Every scene, every sentence, every word should serve to advance the storyline. When editors talk about “pacing,” they refer to the narrator’s ability to keep the reader turning the page.

When you write a book length manuscript you need to keep the story moving forward. Every scene, every sentence, every word should serve to advance the storyline. When editors talk about “pacing,” they refer to the narrator’s ability to keep the reader turning the page.

Have you ever heard someone tell a joke that went on for so long by the time the punch line came you moaned instead of laughed? With comedy, timing is what makes it funny.

It’s hard to recognize good pacing, but readers notice when it is lacking. Pacing is about the manipulation of time in text.

If you are looking for a rule of thumb, this is it: When nothing happens, hurry it up. When there’s action, slow down and spell out every detail.

Avoid summarizing major events. Instead, spell them out with details, particulars, specifics. If you’ve ever been in a car accident, then you know the sensation of time slowing down as the crash occurs. Carry this experience into your writing. The minutes prior to the crash whiz by at 70 mph. The second you lose control of the vehicle, time stretches and warps like slow-motion video. During the climax scene, the number of words you write will be tenfold the number about the passage of several years prior to the crisis moment. What takes only seconds or minutes in real time might be covered in ten paragraphs or ten pages.

Avoid summarizing major events. Instead, spell them out with details, particulars, specifics. If you’ve ever been in a car accident, then you know the sensation of time slowing down as the crash occurs. Carry this experience into your writing. The minutes prior to the crash whiz by at 70 mph. The second you lose control of the vehicle, time stretches and warps like slow-motion video. During the climax scene, the number of words you write will be tenfold the number about the passage of several years prior to the crisis moment. What takes only seconds or minutes in real time might be covered in ten paragraphs or ten pages.

Tempo. Speed. Rhythm.

Tempo. Speed. Rhythm.

Pacing is the part of an author’s composition which involves the structure of time similar to what composers do when they write music. If you think about your book like it is a symphony, you will have three or four movements which make up an entire work. The opening sonata or allegro is usually a quickly, lively, bright piece of music. It sets up for the listener all the music to follow with its exposition and themes. A second movement is usually a slower movement. It may involve variations on the theme introduced in the opening movement. The third movement is usually fast, like a dance, or scherzo. Think about the musical crescendo as the narrative tension rises. The fourth movement is also fast and usually short. Think Coda. It pulls all the elements from the previous movements together into a finale.

There are two literary techniques which writers use to manipulate time and effectively advance the storyline. One is foreshadowing and the other is flashback.

There are two literary techniques which writers use to manipulate time and effectively advance the storyline. One is foreshadowing and the other is flashback.

Foreshadowing can be used to get the reader through a slow section of a narrative. The author hints about what is to come and arouses the reader to find out more. Hints. Signs. Clues. This implies a great deal of subtlety. Don’t tell the reader what will happen. Instead focus on details which might have unusual or particularly emotional significance which will be revealed later.

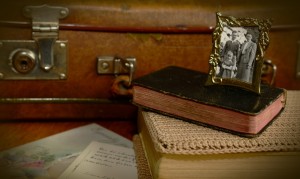

Flashbacks are used to interrupt the chronological order of a narrative with an earlier scene or event which provides background or context to the story.  Because flashbacks are scenes from the past, they involve action and can advance the story line when nothing happens except inside the head of a character who remembers. Pacing drags when the narrator reflects in a telling mode. “I remember how happy I felt when I visited my grandmother as a child.” It picks up when you write a flashback to that snapshot moment of bursting through grandma’s screen door into the aroma of chocolate chip cookies baking and the warmth of her hug.

Because flashbacks are scenes from the past, they involve action and can advance the story line when nothing happens except inside the head of a character who remembers. Pacing drags when the narrator reflects in a telling mode. “I remember how happy I felt when I visited my grandmother as a child.” It picks up when you write a flashback to that snapshot moment of bursting through grandma’s screen door into the aroma of chocolate chip cookies baking and the warmth of her hug.

Foreshadowing and flashbacks are two literary devices, when used judiciously, can positively affect the pacing of your narrative.

Using dialogue is another method to quicken the pace when there isn’t much action. It allows the narrator to reveal information which will instigate action. Readers will wonder “what next?”

Skip the transitions—furthermore, subsequently, similarly, however, first, then, next—and leave them for academic and business writing. They drag down your pace and put the reader to sleep.

Word choice affects timing, too. “Skedaddle” sounds faster than “hurry.” “Meandered” slows the reader’s pace more than “strolled.” Say the words aloud and you will hear the tempo to the word. “Brisk” quickens the pace more than the word “stimulating.”

Varying the length of your sentences affects pacing. Longer sentences with complicated sentence structures which might include dependent and independent clauses will force the reader to slow down the pace of reading in order to ensure comprehension. Short sentences pack a punch.

Punctuation can also help. I’m a big fan of the emdash—in case you hadn’t already noticed. Mary Norris—an editor at the New Yorker whose memoir, Between You & Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen, is one of my favorite books—has a wonderful series of podcasts you might like. There are two episodes about using the emdash. The Mad Dash and the Mad Dash, the Sequel. The emdash often comes in pairs. In the middle of a sentence you are writing—for example, this one—you can have an interjection. It more closely resembles the way we speak and the way our mind races around things. If you have read any Emily Dickinson poetry you can see how the dash or hyphen is used to create timing and pacing in her poems. Using semi-colons can combine two related sentences so they slow the pace down. Periods also can help with pacing. This. Works. Great.

Punctuation can also help. I’m a big fan of the emdash—in case you hadn’t already noticed. Mary Norris—an editor at the New Yorker whose memoir, Between You & Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen, is one of my favorite books—has a wonderful series of podcasts you might like. There are two episodes about using the emdash. The Mad Dash and the Mad Dash, the Sequel. The emdash often comes in pairs. In the middle of a sentence you are writing—for example, this one—you can have an interjection. It more closely resembles the way we speak and the way our mind races around things. If you have read any Emily Dickinson poetry you can see how the dash or hyphen is used to create timing and pacing in her poems. Using semi-colons can combine two related sentences so they slow the pace down. Periods also can help with pacing. This. Works. Great.

Ignore that rule you were taught in high school about the sins of sentence fragments. Use ‘em. Whenever. Clipped. Like a trot. They pick up the pace.

Set off one sentence as a stand-alone paragraph if you want it to have maximum impact.

Attention to verb tenses is my final tip for addressing the problem of pacing. Use present tense where appropriate. Strong active verbs in present tense carry a reader along like a raft in a rapid river. Use simple past tense whenever possible. Avoid using those participial verb forms so common to oral expression in your narration. Instead of “she is going to the store,” write “she goes to the store.” Instead of “he was walking,” write “he walked.” See how many helping verbs you can eliminate to keep the reader on the edge of their seat.

Attention to verb tenses is my final tip for addressing the problem of pacing. Use present tense where appropriate. Strong active verbs in present tense carry a reader along like a raft in a rapid river. Use simple past tense whenever possible. Avoid using those participial verb forms so common to oral expression in your narration. Instead of “she is going to the store,” write “she goes to the store.” Instead of “he was walking,” write “he walked.” See how many helping verbs you can eliminate to keep the reader on the edge of their seat.

Pacing is a feature of good writing you can’t ignore. Keeping the reader’s interest and compelling them to continue is the craft of good timing.

This post is chock full of useful tips! The rule about hurrying up when nothing is happening and slowing down when it gets exciting is the part I’ll take home with me. That’s easy to remember and very effective.

A lot to think about here. Yow. Emdash – yeah. Gotta try some. Cheers!