Blame Aristotle. Blame classical Greek culture. Blame all of Western Civilization. But every story must have a beginning, middle, and end. And more than that.

Blame Aristotle. Blame classical Greek culture. Blame all of Western Civilization. But every story must have a beginning, middle, and end. And more than that.

Without narrative structure, non-fiction writing is just a boring recitation of one thing after another. You may think because it is based on your experiences, historical events, scientific experimentation, or natural observations that you don’t need a story to write a book. Think again.

Fictio, from the Latin, is the heart of writing: to inscribe, shape and mold an inventive or interpretive explanation.

To write non-fiction is to create a coherent tale. For a writer, there are two parts to every telling: story and plot. They are not the same thing. Plot is the structure given to the story. For example, girl meets boy. Familiar story. The plot is that girl gets a new hairdo, leaves salon, drives through traffic looking in rear-view mirror and rear-ends boy in a baby blue BMW. Love ensues.

Archetypal stories, myths, and fairy tales provide a cultural pool from which to remix story structure variations, techniques, and  stylistic flourishes. Shakespeare, the Bible, Greek mythology and stories in popular culture from The Wizard of Oz to the Minions.

stylistic flourishes. Shakespeare, the Bible, Greek mythology and stories in popular culture from The Wizard of Oz to the Minions.

Writers need to find their story first and then figure out how best to tell it. Your job is to let the reader know what they need to know when they need to know it. Not an easy task. Some call it writing craft.

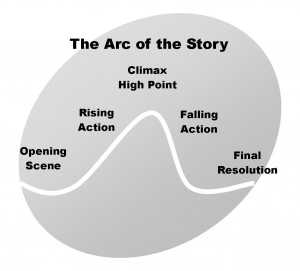

Following Aristotle’s dramatic arc provides a template. Set the scene. Introduce characters and their motives with action scene(s). Establish the premise. Then the inciting incident creates a conflict or challenge. Something happens and instigates further actions.

Plot is the sequence of events. Story is the consequence. One thing should lead to another. A memoir is more than a string of vignettes. History is more than a chronicle of chronological events. Scientific inquiry is not merely a series of loosely related experiments. Across the vertical access of fictio time, from the first page to the last, the reader should feel movement, change, transformation; at least in comprehension of the subject matter.

The tension should rise to a crescendo. Find the turning point to your story – where the solution to the problem becomes evident – and place it three-quarters into your outline. From the crescendo, put into your outline the falling action into a successful resolution of the conflict or challenge. Anti-climactic stories are the ones readers tend to lose interest in and there’s no reason to finish if it isn’t going anywhere. Your devoted reader requires you spell out the ramifications and implications of your findings. What does the reader know now that s/he didn’t before? What is the take-away lesson?

The tension should rise to a crescendo. Find the turning point to your story – where the solution to the problem becomes evident – and place it three-quarters into your outline. From the crescendo, put into your outline the falling action into a successful resolution of the conflict or challenge. Anti-climactic stories are the ones readers tend to lose interest in and there’s no reason to finish if it isn’t going anywhere. Your devoted reader requires you spell out the ramifications and implications of your findings. What does the reader know now that s/he didn’t before? What is the take-away lesson?

Thanks, Jill. I’m finding it’s a good idea to go over this now and again, and keep checking as I revise. I recently interwove the two journeys that comprise my memoir. So keeping a clear narrative arc got harder. Not exactly what a novice writer really needs to tackle, but it definitely made the whole thing more interesting.