POV. Point of View. When you begin to write, you must decide who will tell the story.

You will, of course. Duh. You are the narrator if you are the writer. But who are you? Are you the heroic character? The omniscient voice of God? The fly on the wall? Journalist reporting from the scene? How do you find the right narrator’s voice?

One of the simplest guides to sort through this issue is Spilling Ink: A Young Writer’s Handbook by Anne Mazer and Ellen Potter (Roaring Brook Press, 2010). The two Ithaca area authors intended to write a how-to book for kids who want to write, but I find it a handy desk reference for developmental editing with adult authors. Mazer and Potter spell out POV in one short chapter. They use simple clear language unfettered by highfalutin literary jargon.

One of the simplest guides to sort through this issue is Spilling Ink: A Young Writer’s Handbook by Anne Mazer and Ellen Potter (Roaring Brook Press, 2010). The two Ithaca area authors intended to write a how-to book for kids who want to write, but I find it a handy desk reference for developmental editing with adult authors. Mazer and Potter spell out POV in one short chapter. They use simple clear language unfettered by highfalutin literary jargon.

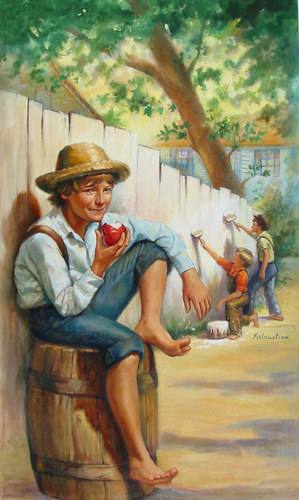

First-person narrative is used in memoir and personal essays. “This is when one of the characters in the story is narrating. It can be a main character or one of the minor characters. You can generally recognize first-person narrative right away because the narrator uses the prounoun I,” writes Anne Mazer on page 67 of Spilling Ink. First-person point of view, however, poses challenges to the writer who can only present the narrator’s experience without comment or the vantage of other characters’ point-of-view. Huck Finn is the classic first-person narrator; the whole story is told in his voice.

Second-person narrative can be confusing to some storytellers. “This is when the narrator talks about ‘you’ as the subject.” You, dear writer, directly address the reader with YOU as the subject of sentences. You often find second-person narrative used in how-to and self-help books. Rarely do you find second-personal narrative in fiction. Aura, by Carols Fuentes, is about a young historian answering an ad in the newspaper. You’re hired to write the memoirs of a 109 year old women who is cared for by her niece, Aura, who is beautiful and whom you fall in love with as you are locked in the house with two women. See how I used second-person to describe this novel? Only occasionally do you use second-person in memoir: Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City and Mary Karr’s Cherry are two examples of writing using this POV. Humor writing, however, often employs second-person narrative. Did you hear the one about…? What do you call a …?

Third-person narrative is frequently the POV of choice for nonfiction narrative writers. But what probably comes immediately to mind is Ben Stein acting the bland science teacher narrating film strips in the TV series, The Wonder Years.

Third-person narrative doesn’t have to be this way. Not so dull. Not so boring.

What I love about Spilling Ink is the explanations for the variations on third-person narrative voices.

Third-person limited is like sitting down on the porch swing and the stranger next to you begins to tell you a story about somebody else. That stranger is the third-person. The somebody else is your main character and third-person limited allows you to get inside the head of your protagonist. It’s a powerful way “to get readers to identify with your main character without using the character’s voice to tell the story, as in a first-person narrative,” explains Ellen Potter on p. 72. Much of the fantasy and speculative fiction genres use third-person limited POV. Mark Twain wrote The Adventures of Tom Sawyer in third-person limited.

Third-person omniscient is frequently used in fiction and nonfiction. “This narrative is the all-powerful, all-knowing point of view,” Potter writes. You can explore a story from all different perspectives with third-person omniscient POV. This narrator sees beyond any one character’s perspective and more than the sum of all the characters vantage points. Often this perspective is chosen to convey a moral or deliver a scientifically persuasive argument.

Third-person objective is another variant of the omniscient POV. “In this narrative, the narrator doesn’t see inside of anyone’s brain. The narrator just describes what the characters do and say, without any emotion. Readers have to figure out what the characters are feeling through their dialogue and actions,” Potter pens. Just report the facts and let them speak for themselves. Imagine how Dr. Spock would narrate. Old school journalism and historical non-fiction embrace this perspective for writing narrative.

Some books have alternating or roving points of view. If there is a shift in first-person perspective from one character in the first chapter to first-person perspective of a different character in the second chapter, and so forth, it is called alternating POV. Louise Erdrich’s Plague of Doves has three unforgettable narrators whose interwoven stories come together to reveal a wrenching truth to the reader. If there is a shift in third-person omniscient from one narrative perspective to the next, then it is called roving points of view.

POV provides the scaffolding for the plot’s architecture.

So, who is your narrator? What is the right narrative voice to tell your story?